His family has belonged to the church for generations, and he was exactly the kind of member Pinckney was trying to bring back to the church, reviving its aging membership and stemming the flow of young people to the big megachurches in the suburbs, where many of them had gone to live. The youngest study group member was 26-year-old Tywanza Sanders - a recent college graduate, barber, and aspiring rapper and motivational speaker, according to the back of his business cards. Daniel Simmons, who was 74 and had come out of retirement to join the ministerial staff at Mother Emanuel, was the study group’s leader and organizer. So did Sharonda Coleman-Singleton, a speech pathologist, girls’ track coach, and part-time minister. Ethel Lance, a Church sexton and usher, stayed. Thirteen people settled at a round table with their Bibles out, and notebooks for particularly salient points about that night’s passage - a serious study for serious Christians.

The Bible study - which typically ran for an hour or two - finally began that night just before 7:30 p.m. Most of the other church members did, too. Dennis had often attended the study, but after the business meeting wrapped up, she went home. In the spring and summer, the hot Charleston sun is up late. Everyone was welcome, but no one would be surprised if you didn’t show up. Between 20 to 25 people might be there any given week, all of them familiar faces, but it was a free-flowing kind of gathering. But Mother Emanuel, as members call it, reserved Wednesdays for a close, intimate study of scripture.

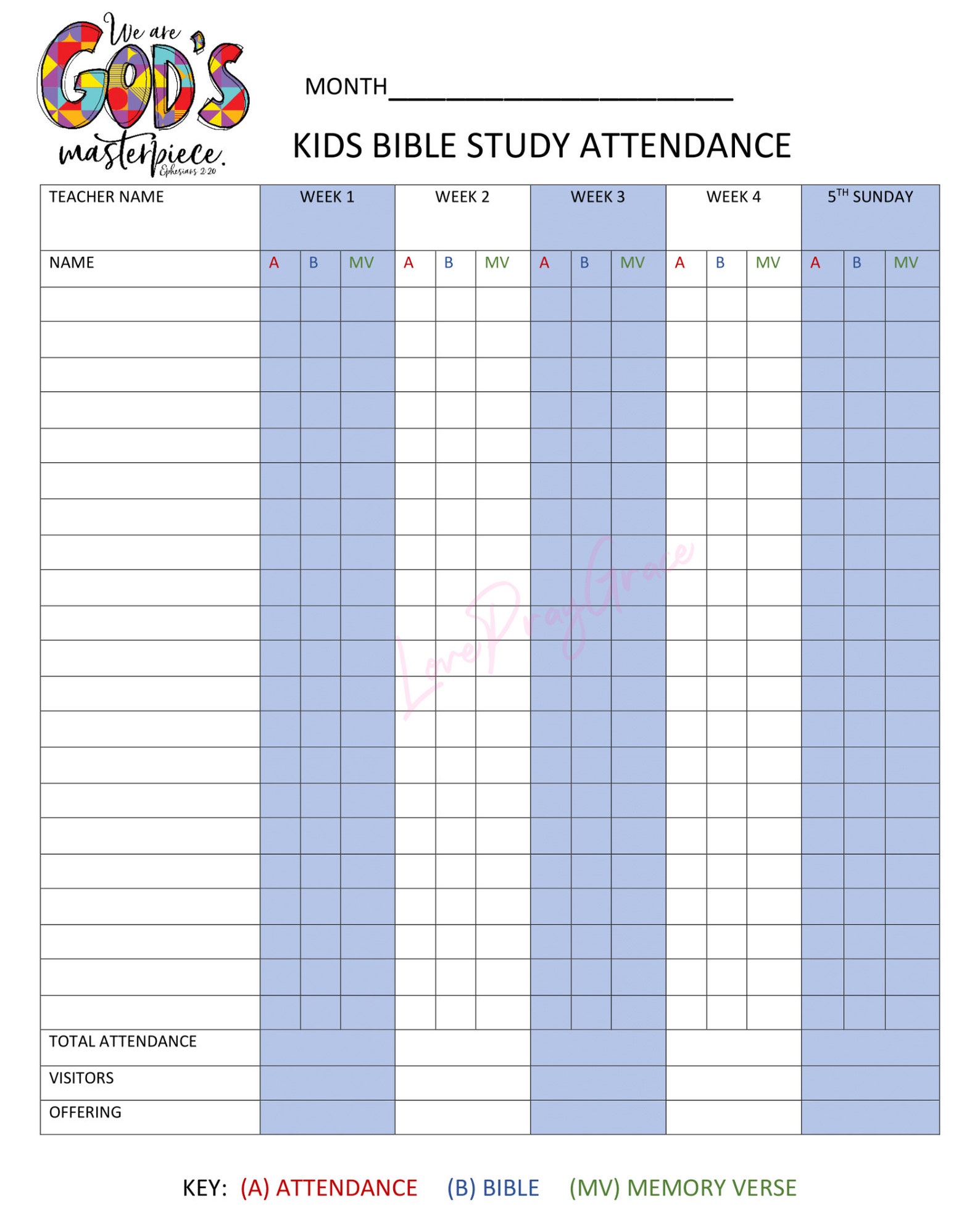

#Bullet in a bible attendance full#

Membership changed, numbers fluctuated, but the Wednesday-night sessions had been a constant.Įlsewhere in Charleston, and indeed throughout the South, churches hold full services on Wednesday nights. The Wednesday-night Bible study had met for as long as anyone could remember. They needed to finish up quickly because the church’s Bible study group was scheduled for later that evening. They went through the agenda, they checked boxes. “I guess … minus nine.”Ībout 50 people showed up for the business meeting. “We have a membership of about 927,” she says, then pauses. Carlotta Dennis, a longtime member and church steward, keeps tally. Church elders, ministerial staff, and other members gathered on the lower-level floor that doubles as the church’s fellowship hall, a big, paneled room with folding chairs and tables that can accommodate the entire congregation.

Clementa Pinckney, the church’s 41-year-old pastor and a state senator, drove down after a legislative session in the state capital, Columbia. A few hours later, as people’s workdays ended, the church began to fill up for a business meeting. On the afternoon of June 17, a construction crew continued work on the church’s new elevator, built to carry aging members up to the sanctuary so they can avoid the long climb up the stairs. – MP, June 2016ĭays have been busy this summer at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in downtown Charleston, South Carolina. In the immediate aftermath of the shooting at Mother Emanuel, the feeling was that we should never allow such a thing to happen again. Meanwhile, attempts to fix the leaks in federal and state gun laws - laws that allow people to buy guns without a completed background check - quickly stalled, again.

Within a month, the Confederate Flag flag was suddenly, finally gone from the statehouse grounds in Columbia. The shooting of nine members of a Bible study group at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church brought forth a steady stream of mourners intent on action. This time last year, I headed to Charleston, South Carolina, in the wake of one of the most stunning mass shootings and acts of racial violence in the United States in my lifetime.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)